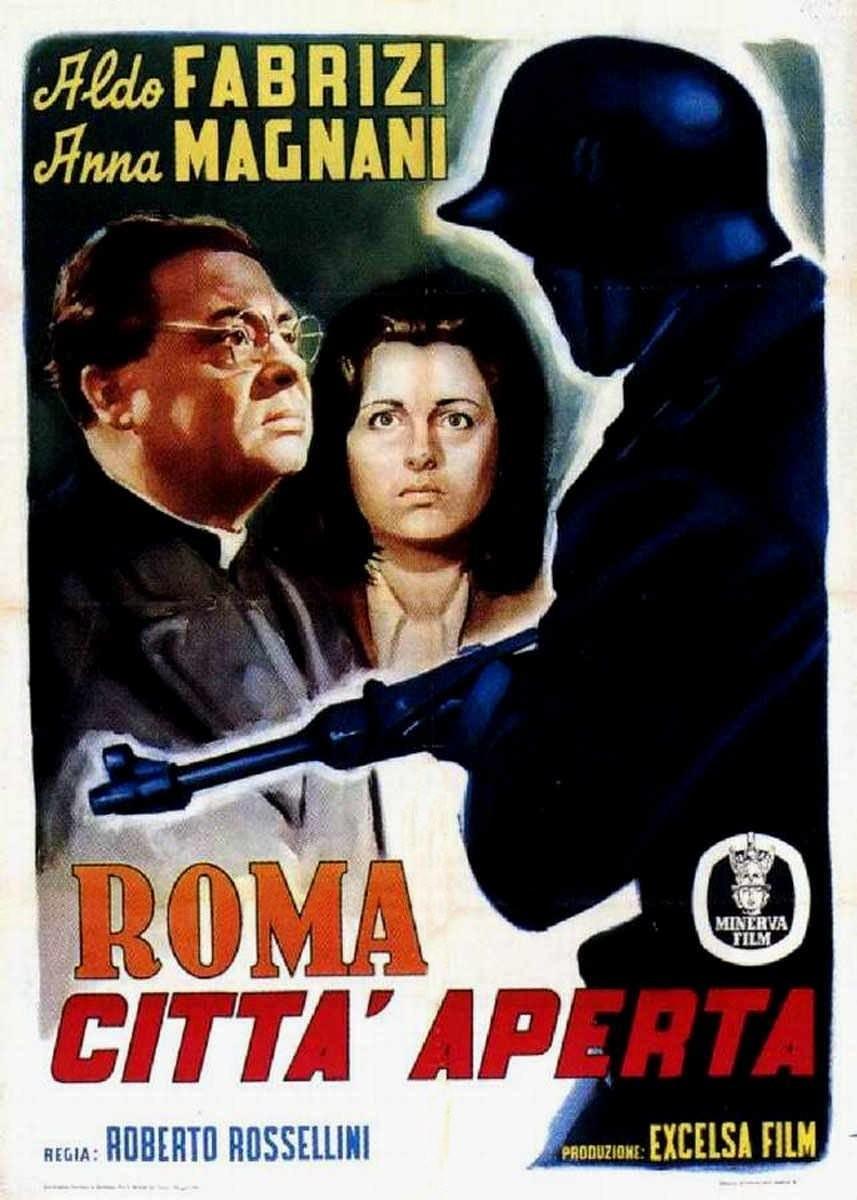

Rome, Open City (1945)

1945, the war has just ended and Roberto Rossellini decided to take everyone right back into it. How raw must the audiences emotions have been watching on the big screen what they just endured for years in their real lives? There are no punches pulled, nothing has been glossed over, there is no romantic vision of war and heroism. Loss, Rossellini seems to say, is the universal constant of real war.

Neo Realism is the cinematic movement that sprung largely from this film in post war Italy. Certainly the economics of the country led to Rossellini and his crew having to be inventive with the production of this film. Scarce film stock, non-professional actors, location shooting, lack of equipment capable of Hollywood-izing the look of a city bombarded by war, all these things gave audiences something they hadn’t seen before. Americans especially, coming from the sanitized and picturesque images of the studio system must have been shocked. We are shown a woman, pregnant out of wedlock, shot down in the street racing after her captured fiancé and a priest executed for keeping his parishes secrets against the questioning of a sadistic gestapo chief. Most disturbing of all is a long torture scene that is quite graphic for its time being juxtaposed with the chic interior of a party amongst gestapo agents going on in the next room.

The story takes place mostly in a building complex where Italian resistance fighters hide out amongst the locals. There is no line drawn between the working class people of Rome and the underground as they all fight and die in the face of Fascism/Nazism. Rossellini deftly shows the children of the building, young boys, as little soldiers. They have seen the perils and desperation of war and take very seriously their role in ending the Nazi occupation. In fact it is their mission, blowing up an oil tanker, which leads the gestapo to the building where they eventually capture the resistance leader. The other focus of the film is catholic faith. The parish priest is drawn in to help the resistance when the Nazi net begins to close around the underground fighters. In one of the more poignant scenes the priest is made to watch while the leader is being tortured. It is through his eyes that we see he understands that like Christ who endured torture and sacrificed his life for his people, so does the brave soldier sacrifice himself for the greater good of Italy.

Neo realism is not documentary filmmaking. Yes real locations are used and real people often fill the screen as opposed to the faces of made up actors, but the filmmaker uses these traits to his narrative advantage. Rossellini is able to maximize the emotion of the audience by bringing us close to the realities and hardships of war. We know how close we are to seeing real atrocities; it is only made bearable by the cinematic undercurrent that separates neo realism from actual documentary footage. The great Italian director Federico Fellini co-wrote the screenplay for this film. He started under the tutelage of Roberto Rossellini and early in his directing career he was linked to the neo realism movement. But Fellini moved more and more into the world of surrealism, maybe after being faced with the stark world Rossellini created in Rome, Open City as well as other masterpieces, Fellini decided he had enough of the “real” world and decided cinema should be an escape. Rossellini didn’t want his audience to escape; he wanted the world to look at the evils that up until then we could only imagine happening in times of war, until he showed it to us.